Hang Right Part 4: The Knowledge Quest—Lessons 2-4

In the second installment of the Knowledge Quest, BD Athlete Sam Elias and DPT Esther Smith dive deeper into the training involved in rebuilding our core, rehabbing injury, and breaking through grade plateaus with this newfound understanding.

In Lesson 1 BD Athlete Sam Elias learned about two very important climbing muscles: the Serratus Anterior and the Latissimus Dorsi. These muscles are essential in the engineering of a proper push-up and pull-up, and they also help to form the critical anatomical link of our arms to our core. This knowledge propelled Sam to want to really “feel” these muscles work and to train them more specifically in order to help continue to rehab his shoulder injury and overcome his redpoint grade plateau.

KNOWLEDGE QUEST LESSON 2:

SO, IT TURNS OUT THAT OUR SHOULDERS ARE OUR CORE TOO?

Redefining the “core” by understanding the arm-to-trunk connection through 3 specific exercises

Sam went on a quest to understand and feel his shoulder anatomy on and off the wall. The missing link for him in regard to shoulder stability was awareness of the arm-to-trunk connection. Sam had a history of shoulder subluxations before this most recent event; thus, he was really zeroing in on what would bring him the most stability while helping him rehab his acutely injured shoulder.

Photos: Andy Earl Illustration: Eli Kauffman

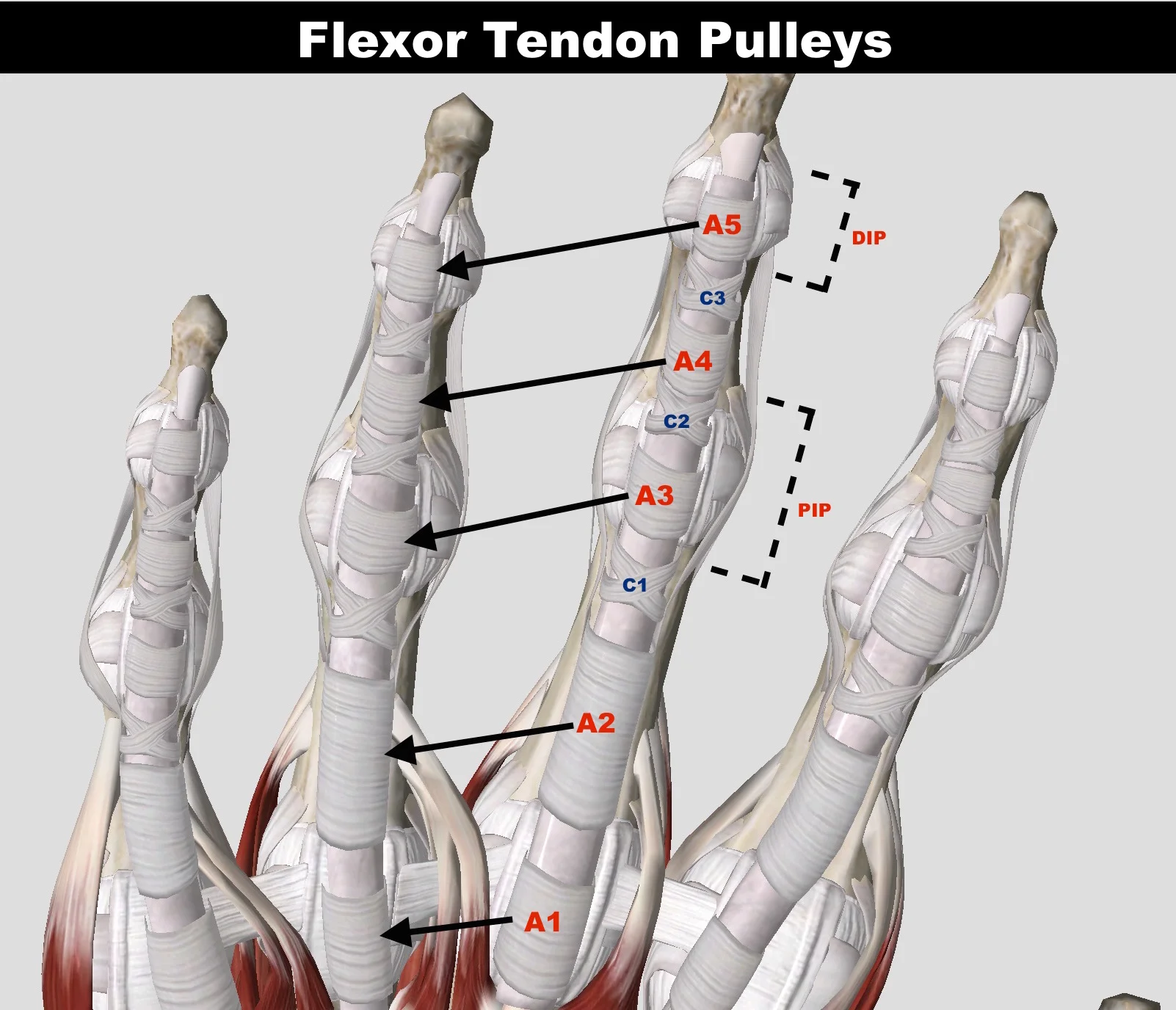

During this quest Sam learned about a serious training oversight. In all of his years of climbing, he never paid much attention to how the trunk and “core” connects to our upper and lower extremities, even while climbing and constantly pulling his trunk up with his arms. Via recognition of the serratus and the Lat, the light bulb went off and these hard to feel, hard to see muscles were illuminated for Sam. These muscles, as part of the core, are the link between the strength of the fingers, hands, and arms into the body.

Finger and elbow injuries are just as common as shoulder injuries, and the shoulder-to-core link can be why. Climbing training philosophy should incorporate finger strength AND core strength for a holistic, well rounded approach. A strong core offers a solid foundation for an upper extremity that is under a lot of demand. Interestingly, Sam felt this disconnect when his shoulder gave out in Hueco, even after a comprehensive and committed training routine.

Through this realization, Sam highlighted a series of three exercises that helped him identify that his shoulder was intimately and physically linked to his core. These three exercises are:

1. SERRATUS PUNCH EXERCISE ON THE GROUND—IDENTIFYING THE “BOXER” PUNCH MUSCLE

A. Lay with back flat on ground.

B. Raise a single arm perpendicular to body and make a fist (you can use a light weight for more sensation/feedback).

C. Punch your fist as far forward as possible towards the ceiling. Feel your scapula wrapping around your ribcage. The fist should go forward and a little inward, and the scapula moves around the ribs.

D. Retract the scapula and fist to the start position.

E. Repeat, feeling the “punch” action of the scapula, and the muscle tone at the side of your ribs under the armpit.

2. ROLLER UP THE WALL—FEEL THE SERRATUS UPWARDLY ROTATE THE SCAPULA AND SLING THE TRUNK SIMULTANEOUSLY

A. Stand in front of a wall with arms outstretched forward and elbows bent at 90 degrees parallel to the wall and to each other with thumbs pointing at your face.

B. Place a foam roller between your wrists and the wall.

C. Push the roller up the wall trying to keep your forearms parallel in all directions (you can use a light band to maintain parallel/shoulder width distance), and your body stacked. The serratus helps the arms “punch” and helps the scapula rotate wide and flush on your ribcage.

D. Go as high as you can, rolling the roller down your arms, stretching your hands up above your head (make sure to let the scapula rotate wide and open, not shrugged towards ears).

E. Pull the roller with the serratus muscle down the wall (roller moves up the arms to the wrists) back to the start position.

3. PUSH-UPS—FEEL THE SLING EFFECT OF THE SERRATUS AND THE CONTROL OF THE SCAPULA

A. Start in a plank position and use the sensation from the punch exercise to keep the shoulder blades far apart and the chest hollow.

B. Keeping elbows in and close to the body, lower down with the triceps keeping the shoulder blades far apart for as long as possible.

C. As the hands get close to the chest, the shoulder blades will naturally need to come together, sliding on the ribcage towards the spine.

D. When you push back up, first create space between the shoulder blades and a hollow chest, then press all the way up with the triceps.

What you learn from these exercises must be transferred to the wall. In lesson 3, we discuss linking the sensation of activating these muscles to climbing movement.

KNOWLEDGE QUEST LESSON 3:

DEVELOPING THE MENTALITY OF NOT “HACKING IT”

Skill development and movement repatterning

Climbing allows us to enter into the sport and get by with certain strengths and weaknesses that we favor because they accelerate the pathway to climbing harder. This method of “hacking it” may allow us to climb harder, but not necessarily climb better. These hacks don’t allow for uniform development of our body and can go unnoticed as we figure out ways of getting by. As a basketball player needs to learn to dribble before they can shoot, we need to develop a strong foundation as climbers in order to climb well and be injury-free long term. Sam illuminates this concept in the following statement: “I don’t want to just do things, I want to do things well ... I want it to look graceful and effortless and I want it to feel that way.” After noticing this, just barely getting by—or hacking it—felt unfulfilling for Sam.

Sam sought out the help of coach and athlete, Will Anglin, co-owner of Tension Climbing in Denver, CO, to help identify his weaknesses and imbalances. Will helped Sam understand the importance of building shoulder stability through skill development on the wall, movement repatterning, body awareness mechanics and progressive loading into the deep/extreme mobility ranges. Will reinforced the idea of the arm-to-trunk “core” connection from Lesson 2, as well as a specific and simple set of mandatory lifts. Will also worked with Sam on the Tension Board by setting problems to systematically test Sam’s shoulder, as well as other strengths and weaknesses. Filming Sam, Will used the Tension Board to mirror various boulder problems that challenged Sam’s weaknesses. This helped to identify several areas that he could target and improve the quality, efficiency, and safety of his movement.

Sam:

Will is a really smart and kind dude, and he’s had two massive shoulder injuries and subsequent surgeries. However, he’s been healthy for 10 years, and slays boulders up to V14. He climbs wide very well and muscly, but still with fantastic technique. I knew I could learn a lot from him, so I connected, and he invited me to visit Denver for a week-long assessment and training. Each day I learned a ton. By the end of the week, I had a game plan, and big jolt of optimism. He helped me to change my whole approach. I knew I had big potential. I trusted myself, and trusted him, and put my head down into the training cycle.

The following summarizes what Sam learned about his mobility weaknesses and how to correct them.

Part 1

Suboptimal movement habit: Sam learned that he had a tendency to climb with his chest down and elbows high. This is a common movement pattern among climbers that can lead to mechanical misuse of the shoulder joint.

Movement repatterning/corrective drill: This concept deeply resonated with Sam on many levels. He needed to climb with his heart, emotionally and physically. He worked on changing his movement patterns on the wall so that he was always climbing with his heart and chest up, and elbows down. The intention and action to move upward allowed Sam to climb with more power and ease, and with less compromise to his shoulder.

Part 2

Suboptimal movement habit: Lack of attention to proper movement during warm-ups, on easy climbs, or when tired.

Movement repatterning/corrective drill: Methodical execution of each climb regardless of difficulty. Slow down, downgrade to the appropriate level even if it’s under your performance threshold in order to practice proper movement. Focus on easy moves and proper movements while fresh. Practice doesn’t make perfect, perfect practice makes perfect. Focus on quality and be honest with yourself-- it’s not just about doing a problem, it’s about doing it right.

Part 3

Suboptimal movement habit: Succumbing to the common pitfall of getting by on strengths and avoiding weaknesses.

Movement repatterning/corrective drill: Sam designed a slow progression of working on movements that were really tough. Starting small and working on wider and wider (more shoulder dependent) moves over time. This takes significant time. Set boulder problems for yourself that you can’t do “cheating” or relying on brute strength or natural talent. Repattern to rely on proper muscle movement.

Slow progressive application of these lessons helped heal Sam’s shoulder. He developed a new brain-body connection through his nervous system via observation on video, sensation on and off the wall, time and perfect practice. This practice eventually resulted in a fulfilling feeling of knowing how he was moving on the wall and not compromising his body and being stronger and safer in bigger ranges of motion.

The other insight that Will gave Sam was that he needed to move away from mild resistance band exercises and begin to train his shoulder stability under heavier loads in all directions.

KNOWLEDGE QUEST LESSON 4:

CLIMBERS ARE SUPPOSED TO BE LIGHT RIGHT? HAS WEIGHT LIFTING BECOME A CLIMBER'S TABOO?

Redefining shoulder strength with the concept of big muscle development via weightlifting vs. small muscle development

Applying his newfound knowledge of anatomy and subtle movement, Sam refined his classical understanding of shoulder strength. Similar to most climbers, Sam historically relied on band and body weight exercises for his shoulder antagonist muscle strengthening regiment. These exercises are typically prescribed after a shoulder injury and are essential in the early stages of recovery. However, weight lifting is often a missing link in strength training that helps us rebuild to our optimal level of function and performance.

Luckily for Sam, coming from a ski racing past, he was already comfortable in the weight room. This is not the case for most climbers, and there are rules in the climbing world that glorify being ultra light. Weight lifting teaches you to work under load, maintain perfect form and body alignment and put forward effort in multiple directions. This is especially important for mobile joints like the shoulder.

Will instilled the philosophy in Sam of exploring broader ranges of stability, touching into the limits of range of motion, but not dropping into dangerous joint positions. He did this by pausing and holding at the apex of lifts and going slow with focus on form, control and eccentric strength. The main lifts are the “Big Four” exercises. They target the key push and pull actions of our arms and shoulder, and also help to develop a uniform and integrated body from our hands to core to toes. They are meant to build raw strength. Will also taught Sam a variety of accessory lifts which supplement the “Big Four,” and are meant for stability, mobility and core. These lifts brought all of the lessons together for Sam and gave him confidence in his shoulder strength, both in the weight room and on the wall.

BIG FOUR LIFTS:

Weight lifting form and parameters are complicated and need to be tailored to each individual. We recommend seeking out professional training advice in your area for detailed instruction and a personalized plan.

STANDING BARBELL (BB) OVERHEAD PRESS

BAR WEIGHTED PULL UP

BB BENCH PRESS

BB BENT OVER ROW

EXAMPLE ACCESSORY LIFTS:

DUMBBELL FLY

REVERSE DUMBBELL FLY (THUMBS DOWN & PALMS DOWN VARIATIONS)

TRICEPS EXTENSION TO LAT PRESS

EGGROLL

Sam:

I came out of training absolutely destroyed. Over-trained in fact. However, my shoulder felt better than ever, and I was pain free. The trip to Spain that I hoped to be in supreme shape for turned out to be a recovery and an adaptation period. I was so tired and slow, and moving really poorly the whole time. It got better every day, and by the end of the trip I started to feel pretty good. Once back in the states, I made my way to Rifle. I quickly did Bad Girls Club (5.14c) and started to try Shadowboxing (5.14d). It’s a route that I’ve tried for many years, but never earnestly, because it seemed too difficult. This year, I made quick progress, and surprisingly sent without much of an ordeal.

I smiled when I received Sam’s June 26 correspondence to me via text:

I flew from SLC to Grand junction on Saturday, drove into Rifle canyon and warmed up, and then smashed the #*^& out of my 5.14d project!

The lessons that Sam learned on his journey from shoulder injury to recovery to return-to-sport can be transferable to all climbers and other types of injuries. Recalling Sam’s lessons when navigating injury can help guide us through the scary and intimidating process of healing and making decisions about our course of care. With the right team of expert providers, Sam took ownership of his body and did everything in his power to gain knowledge and make necessary changes in his engrained movement patterns and training habits. This helped him not only to heal, but also to grow stronger, more confident and more versatile as an athlete and as a person.

Sam:

Everything came together, and it goes to show that injury doesn’t have to be an end point. It can be a starting point, a chance to reconsider everything, and make valuable changes. Progression of any kind, including healing, takes time. It’s best to be patient, and go step by step, moment by moment.